Variation in the shape of speech organs influences language evolution

Why do languages sound so different, when people across the world have roughly the same speech organs (mouth, lips, tongue and jaw)? Does the shape of our vocal tract explain some of the variation in speech sounds? In extreme individual cases, it clearly does: when children are born with a cleft palate, the roof of the mouth is not formed properly, which affects their speech. However, it is unclear whether subtle anatomical differences between normal speakers play a role. Language and speech are also shaped by repeated use and transmission from parents to children. As language is passed on to new generations, small differences may sometimes be amplified. This observation led a team based at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, to ask “what happens when tiny differences in vocal tract anatomy “meet” cultural transmission?”

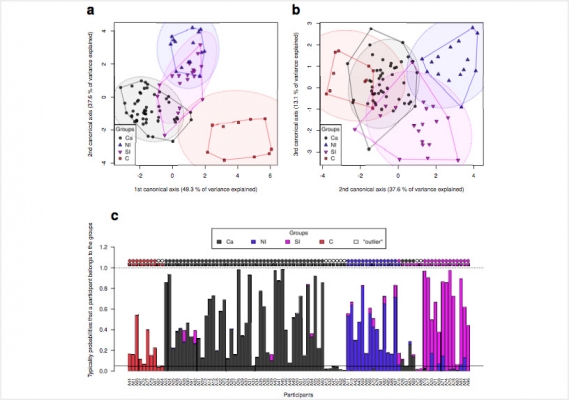

The team decided to focus on whether the shape of the hard palate might influence the way vowels were learned, articulated and passed on across generations of artificial agents. Because changing the shape of the hard palate in human participants is ethically and practically problematic, the scientists opted for a computational study, adapting an existing computer model of the vocal tract. The team imported actual hard palate shapes from more than one hundred MRI scans of human participants into the computer model. With machine learning, they trained agents to articulate five common vowels, such as the ‘ee’ sound in “beet” and the ‘oo’ sound in “boot”. Next, a second generation tried to learn these particular vowels, which were then passed on to the next generation, and so on for fifty generations. “This simulates a simple model of language change and evolution in a computer”, explains co-author Rick Janssen, currently machine learning specialist at ALTEN and Philips Research in The Netherlands. Would subtle anatomical differences in palate shape lead to differences in pronunciation? And crucially, would these differences become more pronounced through repeated transmission?

Biology matters

The subtle differences in the shape of the hard palate did influence how accurately the five vowels were articulated. Importantly, the cultural transmission of speech sounds across generations amplified these small differences, even though the agents actively tried to compensate for their hard palate shape by using other articulators (such as the tongue). “Even small variations in the shape of our vocal tract may affect the way we speak, and this may even be amplified – across generations – to the level of differences between dialects and languages. Thus, biology matters!”, explains the lead author, Dan Dediu, currently at the Laboratoire Dynamique Du Langage, Université Lumière Lyon 2 in France.

According to the authors, this result may also help us better understand the effects of anatomical variation on speech and how to correct it when desired, for instance in case of speech pathology, forensic linguistics, dentistry and post-surgery recovery. But most importantly, the study highlights the importance of individual variation in speech and language in the context of our universal similarities: Co-author Scott Moisik, currently at the School of Humanities, Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, concludes: “while we are all humans and fundamentally the same, we are also unique individuals, and one can really hear it”.

Publication

Dediu, D., Janssen, R., & Moisik, S. R. (2019). Weak biases emerging from vocal tract anatomy shape the repeated transmission of vowels. Nature Human Behaviour. doi:10.1038/s41562-019-0663-x.

Share this page